Some of my more ambitious machine-learning colleagues often have a tendency to get misty-eyed and talk about language as the “next frontier” of artificial intelligence. I can completely agree at a high level: building practical language-enabled agents which can use real language with real people will be a huge breakthrough for our field.

But too frequently people seem to see language as a mere box to be checked along the way to general artificial intelligence. As soon as we break through some perplexity floor on our language models, apparently, we’ll have dialogue agents that can communicate just like we do.

I’ve been exposed to this exhausting view often enough1 that I’ve decided to start working to actively counter it.

What does it mean to “solve language?”

I’m not even sure what people are trying to say when they talk about “solving language.” It’s as vague and underspecified as the quest to “solve AI” as a whole. We already have systems that build investment strategies by reading the news, intelligent personal assistants, and automated psychologists which aid the clinically depressed. Are we done?

It depends on your measure of done-ness, I suppose. I’m partial to a utilitarian stopping criterion here. That is, we’ve “solved language” — we’ve built an agent which “understands language” — when the agent can embed itself into any real-world environment and interact with us humans via language to make us more productive.2

On that measure we’ve actually made some good progress, as shown by the linked examples above. But there’s plenty of room for improvement which will likely amount to decades of collaborative work.

If you can show me how your favorite NLP/NLU task connects directly to this measure of progress, then that’s great. I unfortunately don’t think this is the case for much current work, including several of the tasks popular in deep learning for NLP.

(See the addenda to the post for some juicy follow-up to the claims in this section.)

Situated language use

If I believe in the definition of “solving language” given above, I am led to focus on tasks of situated language use: cases where agents are influencing or being influenced by other actors in grounded scenarios through language.

This setting seems extremely fertile for new language problems that aren’t currently seriously considered as major tasks of understanding. I’ll end this post with a simple thought experiment demonstrating how far behind we are on real situated tasks — or rather, how much exciting work there still is to be done!

Generalization in reference games

Here’s a simple example of situated learning that should reveal the great complexity of language we have yet really to start solving.

Consider a Wittgensteinian reference game with two agents, Alexa and Bill. Alexa is using words that Bill doesn’t know to pick out referents in their environment. It’s a cooperative game: Alexa tries to use words that will make Bill most successful, Bill knows that Alexa is cooperating, Alexa knows that Bill knows that she is cooperating, and so on.

Round 1

Alexa selects some object in the environment and speaks a word to Bill, say, BLOOP. Here’s what Bill has observed in this first round of the game:

Possible referents:

Alexa said: BLOOP

Now Bill has to select the object he thinks Alexa was referring to. The dialogue is a “success” if Alexa and Bill pick the same object.

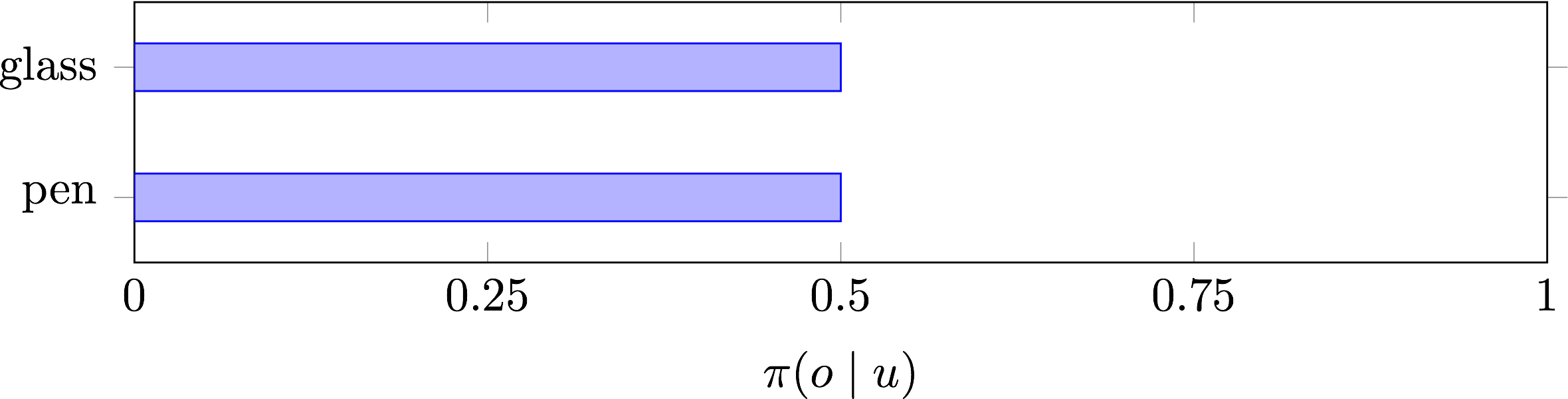

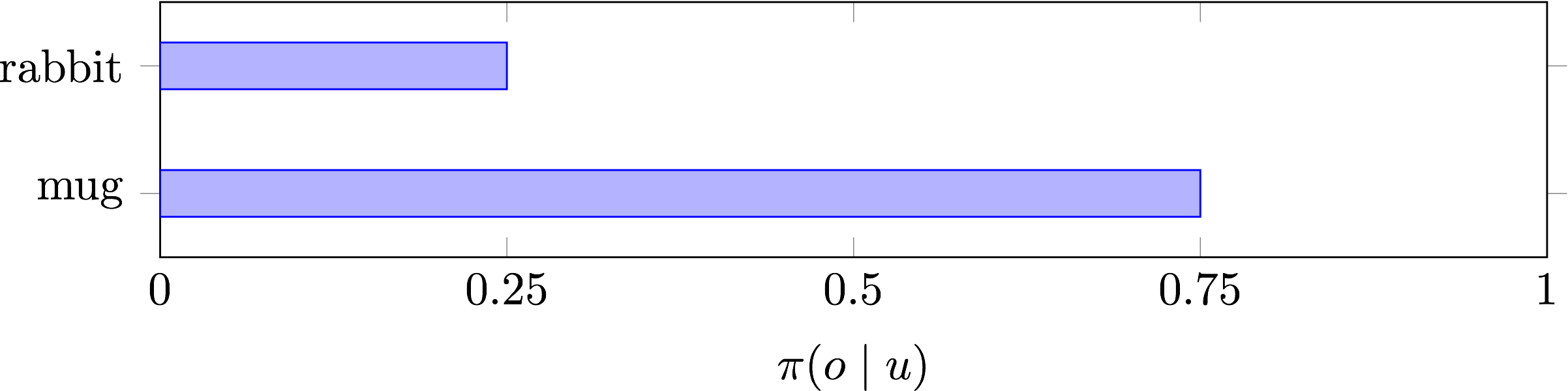

Suppose Bill has to predict some distribution over the objects given Alexa’s utterance \(\pi(o \mid u)\). Since Bill doesn’t know any of Alexa’s words in the first round, we would expect his distribution then to be roughly uniform:3

Let’s say he randomly chooses the cup, and the two are informed that they have succeeded. That means Alexa used BLOOP to refer to the cup. Both internalize that information and proceed to the next round.

Round 2

Now suppose we begin round 2 with different objects. Alexa, still trying to maximize the chance that Bill understands what she is referring to, makes the same utterance: BLOOP.

Possible referents:

Alexa said: BLOOP

I would argue that, despite the fact that both objects are novel (at least at a perceptual level), Bill’s probabilities would look something like this:

What happened? Bill learned something about Alexa’s language in round 1: that her word BLOOP can refer to a glass. In round 2, he was forced to generalize that information and use it to pick the most cup-like object among the referents.

What just happened?

How do we model this? There’s a lot going on. Here are the three most important properties I can recognize.

- As is often the case in reference game examples, Bill had to reason pragmatically in round 2 in order to understand what Alexa might mean.

- This pragmatic reasoning relied on a model of the world. Bill had to reason that the mug was similar to the cup, not because they look alike but because they are both used for drinking.4

- Bill made his inference using a single previous example. This inductive inference relied mostly on his model of the world, as opposed to an enormous dataset of in-domain examples.

These are three basic properties of Bill the language agent. These are three properties that we haven’t come anywhere close to solving in a general way.

(These goals have been recognized in the past, of course; there’s been some good recent work on the specific problems above. But I think these objectives should get much more focus under the utilitarian motivation underlying this post.)

Conclusion

That rather long example was my first stab at picking out situated learning problems, where language is a mean rather than an end in itself. It’s just one sample from what I see as a large space of underexplored problems. Any language researcher worth her salt could engineer a quick solution to this particular scenario. The real challenge is to tackle the whole problem class with an integrated solution. Why don’t we start working on that?

Keep posted for updates in this space — I’m working hard every day on projects related to this goal at OpenAI. If you’re interested in collaborating or sharing experiences, feel free to get in touch via the comments below or via email.

Acknowledgements

I’ve been mulling these ideas over for most of the summer, and a whole lot of people from several institutions have helped me to sharpen my thinking: Gabor Angeli, Phil Blunsom, Sam Bowman, Arun Chaganty, Danqi Chen, Kevin Clark, Prafulla Dhariwal, Chris Dyer, Jonathan Ho, Rafal Jozefowicz, Nal Kalchbrenner, Andrej Karpathy, Percy Liang, Alireza Makhzani, Christopher Manning, Igor Mordatch, Allen Nie, Craig Quiter, Alec Radford, Zain Shah, Ilya Sutskever, Sida Wang, and Keenon Werling.

Special thanks to Gabor Angeli, Sam Bowman, Roger Levy, Christopher Manning, Sida Wang, and a majority of the OpenAI team for reviewing early drafts of this post.

The sketch images in the post are taken from the TU Berlin human sketching dataset.

Addenda

Many of my trusted colleagues who reviewed this post made interesting and relevant points which are worth mentioning. I’ve included them in a separate section in order to prevent the main post from getting too long and full of hedging clauses.

- I claimed in this post that work in natural language understanding often seems too disconnected from the real downstream utilitarian goal—in the case of our field, to actually use language in order to cooperate with human beings. Roger and Sam pointed out that many people in the field do feel this to be true at a broader scale — that is, there are several such related divergences (e.g. the divergence between modern NLP and its computational linguistics roots) that ought to be unified.

- Chris pointed out that there are other uses of language which could be used to likewise argue for different lines of research. For example, language also functions as an information storage mechanism, and my situated approach doesn’t capture this. We can actually use this information-storage view to motivate many of the tasks central to NLP or, more specifically, information extraction.

-

It’s a view that’s quite hard to escape in Silicon Valley for sure. I actually wasn’t able to find the clarity to write this post until now, after a week of travel and late-night conference discussions in Europe. ↩

-

I’m aware this is not only a utilitarian aim but also an anthropocentric one. I’m not sure it’s totally right, and am certainly open to belief updates from my readers. ↩

-

Interestingly, if both Alexa and Bill have English as a native language, I would guess that phonaesthetic effects would lead Bill to prefer the round object over the long, pointy one. That’s how I would behave, anyway. Don’t ask me how to model that. ↩

-

Importantly, this is more than a linguistic model. The facts which Bill exploits are nonlinguistic properties learned from embodied experience. ↩